Potholes Manifest from Winter Freezes

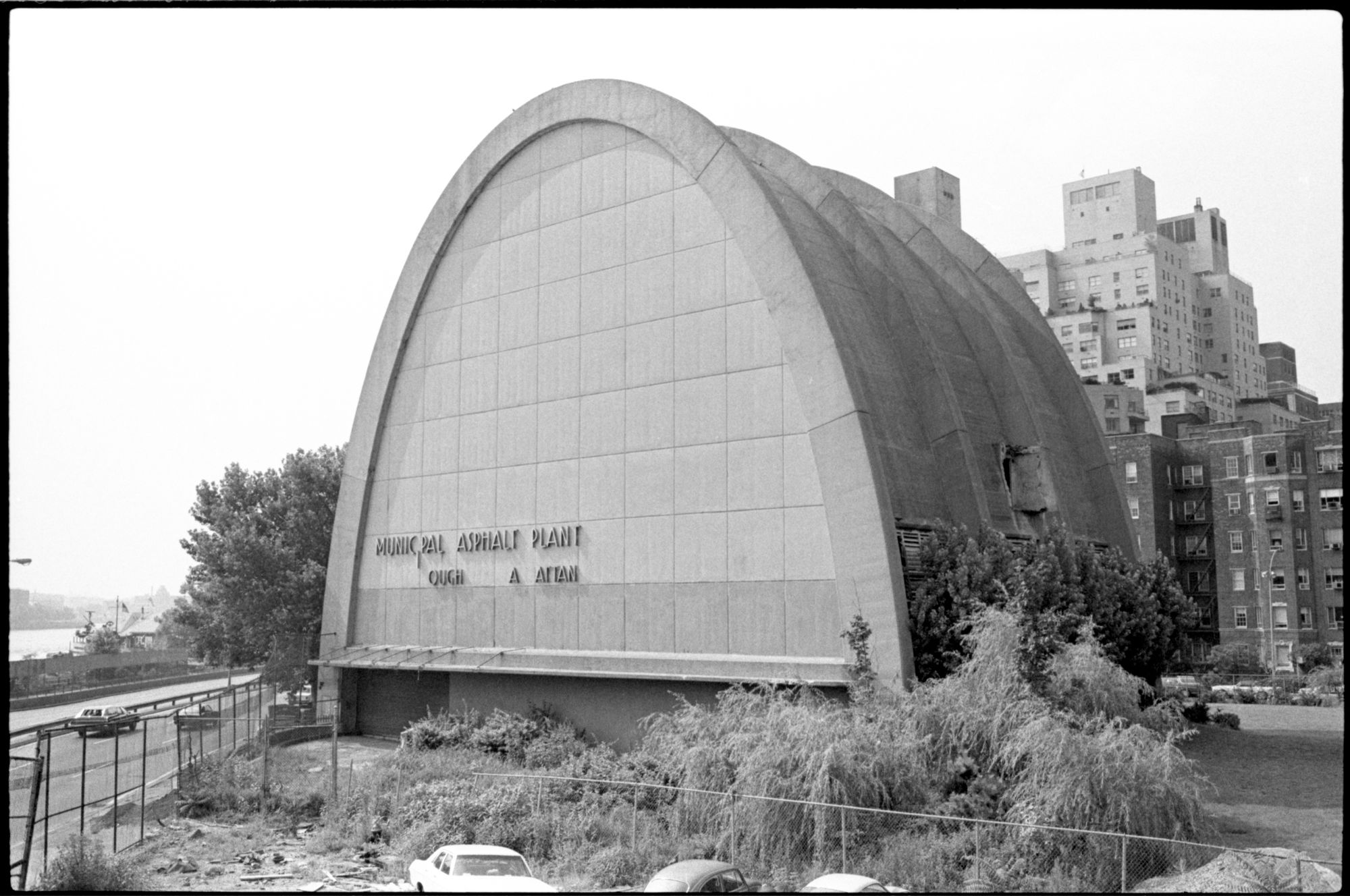

You know spring is truly on the cusp in NYC when the roads crack open with circular holes waiting to rattle and jar drivers and bicyclists (and perhaps twist a few pedestrian ankles). Over the winter, water gets into the asphalt and the ground, freezing and expanding, weakening and cracking the surface. This is accelerated by a shortfall in resurfacing so by spring, streets across the city are pocked and scarred. It’s reported that the city has hundreds of thousands of potholes a year; a monumental annual rite of repair.

Look closely at them, see the human-made strata exposed. Maybe they have gouged deep enough to lay bare old Belgian block paving stones. Once the most common paving material in the city, the regular sizes of the blocks made in the 19th century from—despite their European name—New Jersey traprock from the Palisades were a huge improvement on the uneven cobblestones. (And easier on the ears, too, compared to the clatter of carriages over the more irregular stones.)

Maybe the pothole has collected random street detritus: coffee cups, subway tickets, a person’s keys. Maybe it has filled with water from a recent rain or snow, offering new reflections of the surrounding city. Or it is a murky void, its depth only revealed to those unfortunate enough to step in its gaping maw.

- Icy water has been reshaping the city terrain for millennia. Visit Inwood Hill Park in Manhattan to find the glacial potholes that burrow through the rock, a formation caused by the melting of the Wisconsin glacier some 50,000 years ago.

- The city streets and sidewalks aren’t all concrete and asphalt; some historic geological variety endures. Walk over slabs of granite around Hudson Street, bluestone flag on Bleecker Street, travertine splayed out in front of Midtown’s Grace and Solow buildings, and a black and white terrazzo design by Alexander Calder on Madison Avenue between 78th and 79th streets.

- Lest your wheels be flattened by a pothole’s kiss, you may require the services of one of the flat tire fix joints lining Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Stretches of Manhattan’s 10th Avenue (now replaced by Hudson Yards) and Queens’ Willets Point (where the whiff of gentrification hangs amidst the dust of ceremonial groundbreaking) were once hubs of hubcaps, meccas of mechanics. So, when you now pass stacks of patched spares and all-terrain treads, genuflect to Vulcan (surely the god of rubber repair) and the tire experts within. Request their protection against ravaged asphalt and send warm wishes for their own survival.