Subway Waterfalls Cascade Over Commutes

Even on cloudless days the subway is wet. Millions of gallons of water are pumped out of it each day. The drip of groundwater seeps into the tunnels. Forgotten natural springs ruin signal boxes and cause delays, these long covered parts of the city’s original topography having their revenge on the infrastructure that bored through their homes.

Then there are the rains. Summer showers overwhelm the systems and cascade through the entrances. Stairway steps are transformed into rushing waterfalls. You cannot stay on the platform where the water pools. Have you worn rain boots? Did you check the forecast? Or will you wade perilously in as the murky water soaks your shoes?

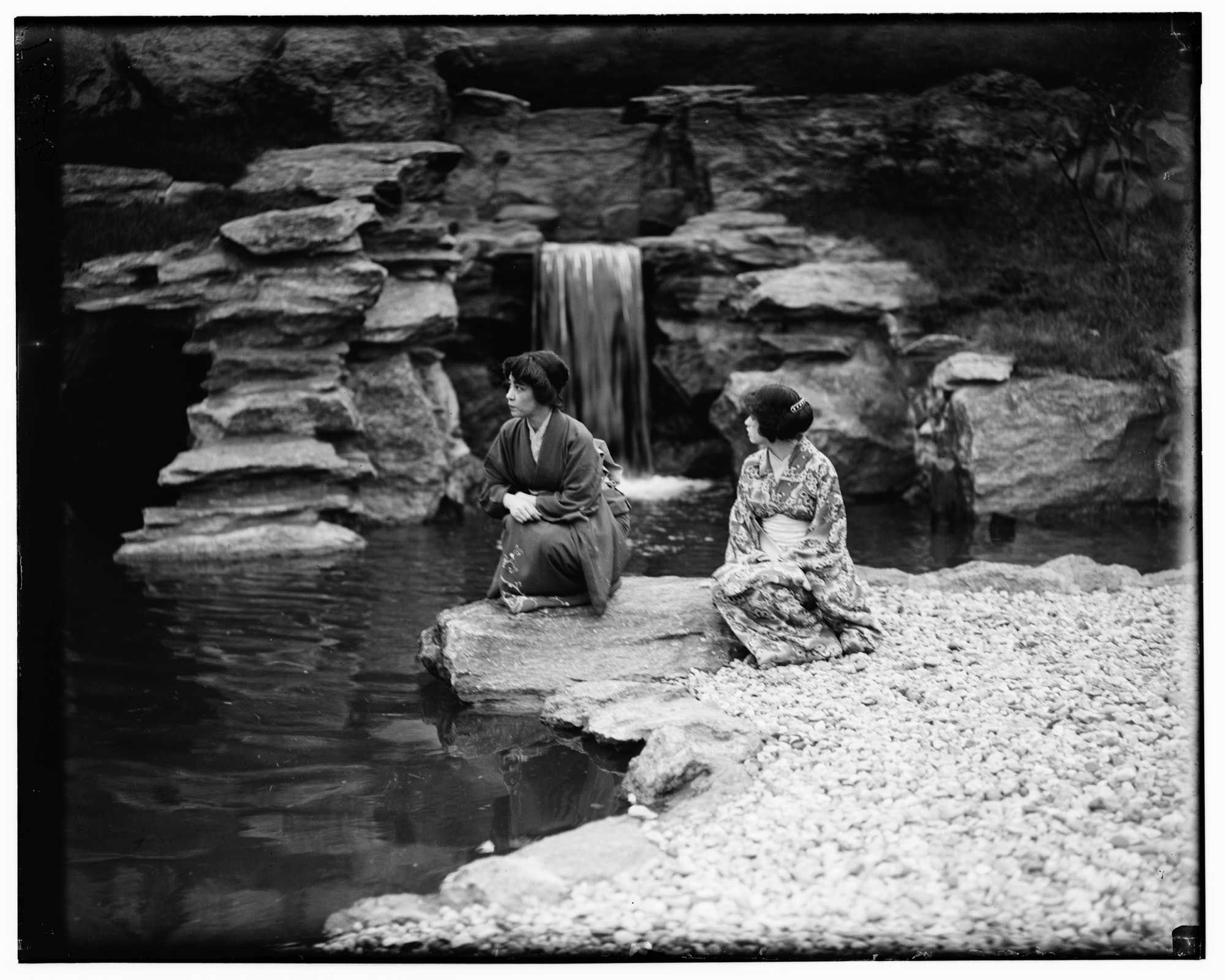

Despite the unnatural appearance of these infrastructural cascades, being part of our weather, they are actually somewhat more natural than the waterfalls in Central Park. Look closely for instance at the picturesque falls in the Hallett Nature Center and you’ll see their source: a pipe. The waterfalls can be turned on and off for the season, with these human-designed falls going dormant for the winter and then being activated in spring.

- Take a tour of other unnatural waterfalls that won’t ruin your commute: The tiny Paley Park drowns out the Midtown noise with its 20-foot-tall waterfall, Greenacre Park on East 51st Street has a 25-foot-tall waterfall that cascades over granite blocks, and the McGraw-Hill Building has a tunnel that cuts through its 40-foot-wide waterfall. The series of waterfalls in the fountain in Albert Capsouto Park recall the canal that was once on Canal Street. However, the most dramatic waterfall design was back in 2008 when artist Olafur Eliasson created a waterfall that plummeted off the Brooklyn Bridge.

- The distinctive smell of rain is called “petrichor.” It was coined by Australian CSIRO scientists Isabel (Joy) Bear and Richard Thomas in 1964, deriving from the Greek for stone (“petra”) and for the blood of the gods (“ichor”) to evoke that earthy scent caused by the mixture of rain, plant oils, ozone, and geosmin (a chemical produced by soil bacteria).

- A network of lunar-lander-looking weather stations spans our city, courtesy of the New York City Micronet. ConEd and New York State operate 22 monitoring sites on the ground, on rooftops, and even on a pier. Bookmark the link to feel like you have your own mini climate mission control for NYC—images are updated about every five minutes, so while you may see the sun still shining in Queens, as rain lashes Manhattan, you can precipitously prepare for precipitation.