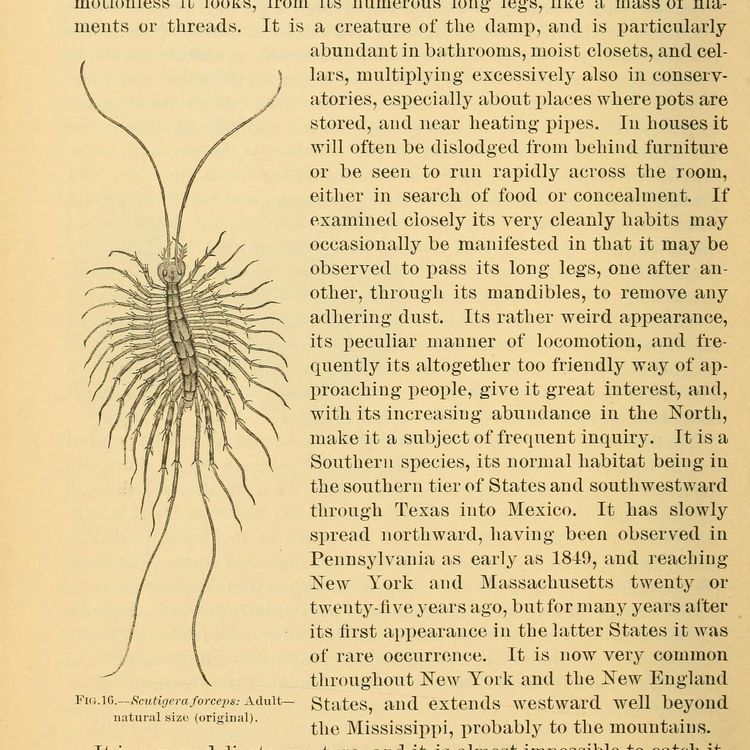

Peregrines Nest at Perilous Heights

Peregrine falcons prefer to have their nests—or eyries—high on cliffs; in New York City, they find homes on skyscrapers and bridges. Nest boxes created especially for them, with gravel so they can make the scrape where they lay their eggs, are positioned at the top of bridges, and maintenance workers are careful not to disturb them as they nurture their broods. They thrive in the city not only because of its variety of dizzying perches but also due to its constant smorgasbord of their favorite food—smaller birds—particularly the pigeon. Soaring high above, they wait for the right moment, tuck in their wings, and dive at speeds reaching 200 miles per hour—the fastest speed of any animal—to snatch the unfortunate prey. Then they feast, sometimes right on the sidewalk amid commuters and LinkNYC kiosks, before returning to the skies.

It was not always like this. By the early 1960s, the peregrines had vanished from the East Coast due to the pesticide DDT getting into their food supply. It was only through a dedicated captive breeding program that they rebounded. In 1983, they returned to New York City, nesting on the Verrazano-Narrows and the Throgs Neck bridges, and have increased their numbers ever since, becoming the largest urban population of the birds in the world.

They mate for life, returning each spring to a preferred bridge tower or skyscraper ledge. As of 2019, there were 25 known pairs. The chicks, with their big, hungry eyes and eager beaks to match, and bodies covered in tufts of white feathers, are rarely seen by New Yorkers unless you also are privileged enough to live in a peregrine-height penthouse. But we can envision what it is like to learn to hunt amid the buildings and streets. Find a pigeon strutting about or a sparrow flitting around a tree, and look up. If you were a peregrine, where would you wait and watch? When would you plunge from the sky to grasp this soft body with hooked claw? We too often focus on the city at eye level, but from above, these birds are hunting: watch for them, and if you are lucky, see their incredible flight and imagine the wind on your face and the city rushing around you.

- “The Falconer” by English sculptor George Blackall Simonds is one of several bronzes that were added to Central Park over the years to evoke a rustic environment, but the bird that takes flight from the Elizabethan man’s hand does not date to its original 1871 casting. That falcon was sawed off along with the arm in 1957. A replacement was also stolen. After spending time in storage, the beleaguered sculpture was resurrected in 1982 with a new arm and a new falcon, which, so far, soars to this day.

- In 1989, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the NYC Department of Environmental Protection started building falcon nesting boxes, which have since hosted more than 100 hatchlings. This year, celebrate raptors on Staten Island by enjoying Port Authority’s live cam of weird fluff balls near the Bayonne Bridge or catch a Ferry Hawks game (perhaps versus the Long Island Ducks or Charleston Dirty Birds?).

- Peregrine falcons are not the only birds of prey to have bounced back in NYC. Bald eagles have been witnessed in all five boroughs in recent years, from Central Park to the pine trees in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, a huge rebound from the 1970s, when there was just one pair of bald eagles nesting in the entire state. DDT, which had thinned the shells of their eggs while they were still in their bodies, and a loss of waterfront habitat to development had wrecked their populations. But the banning of DDT and programs to save the birds, including eaglets being released in Inwood Hill Park, have made eagles once again part of the city’s avian population, including sightings in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park this year.