The Flowering of New York’s Great Old Ones

The tuliptrees are the city’s living elders, growing taller than the other trees, surviving for centuries as other beings live and die in generations around them. And each year they bloom green, yellow, and orange tulip-like flowers that have barely changed in shape and form since when dinosaurs lumbered over the land.

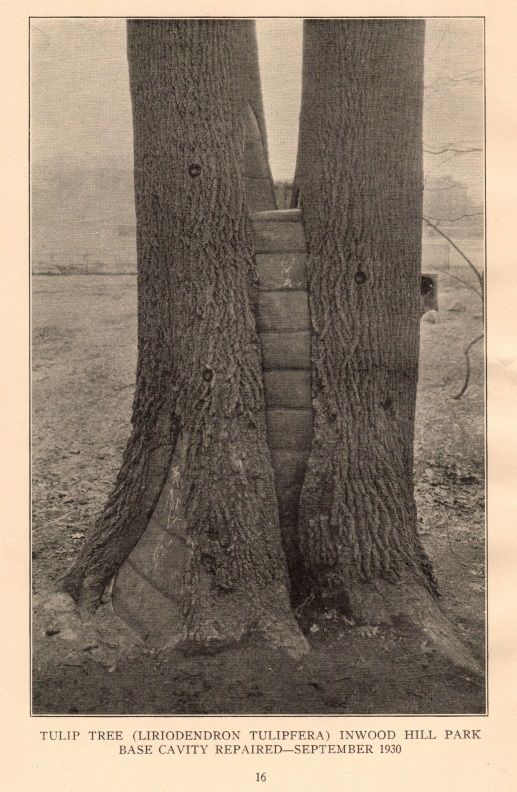

They were there at the city’s beginning, with one said to have presided over the exchange in 1626 between the director of the Dutch colony of New Netherland Peter Minuit and the Indigenous people that was interpreted by the colonists as the sale of Manhattan. That tree held on until 1938, witnessing the languages shift around it from Dutch to English, the city sprawling further and higher, as it grew, too, to over 160 feet tall. A boulder in Inwood Hill Park commemorates where it once stood, a concrete ring marking the width of the lost tree’s gargantuan trunk. Other great old tuliptrees endure and have been anointed with names suggesting something otherworldly and mythical: the Alley Pond Giant of Queens, the Clove Lakes Colossus of Staten Island.

Is there a tuliptree near you? As they grow higher and higher, they lose their lower branches and so those cup-shaped flowers can be hard to see. Look on the ground: no other leaves are like theirs: four-lobed and mask-like, bright green in summer, a vivid yellow in the fall. In winter, you might find the pinecone-esque spikes that were once inside their blossoms. Pick up a leaf; it may be larger than your hand. Look up, do you see a candelabra of branches raised to the sky? What is the view from up there? How far can the tuliptree see across the city, into the future, into years it will witness long after we are gone?

- A tuliptree plays a crucial role in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Gold-Bug,” and he must have been a devotee, as he referenced the species again in his final work—an uncharacteristically unmacabre tale of a countryside idyll written in the year of his death. “Nothing can surpass in beauty the form, or the glossy, vivid green leaves of the tulip-tree. In the present instance they were fully eight inches wide; but their glory was altogether eclipsed by the gorgeous splendor of the profuse blossoms,” quoth the rapturous writer in “Landor’s Cottage.”

- The lofty columns of tuliptree trunks might recall the towering cylinders of a pipe organ, and indeed, tuliptree wood is favored in the construction of such instruments. Our city’s largest is one of the Æolian-Skinner pipe organs at St. Bart’s on Park Avenue. The names of the notes created by the 12,422 pipes can be mellifluous—Flûte Magique, Dulzian, Viole Celeste—or imposing—Holzgedeckt, Flauto Mirabilis, Bombarde. Attend an organ recital and listen for the echoes of wind blowing through tuliptree branches.

- Alley Pond Park, home to the aforementioned Alley Pond Giant, may owe the success of its thriving forest (at least in part) to flaming automobiles. In the 1990s, Parks Department employees dragged hundreds of vehicular carcasses from park land, many only after combustion. The open space created by these unconventional burns allowed some species to thrive. No phoenixes arose from the urban ashes, but rare plants sprung up in their wake. Walk the Tulip Tree Trail at Alley Pond Park and consider the unique intersection of city and nature that supports us.