Fireflies in Multitudes Signal Their Desires

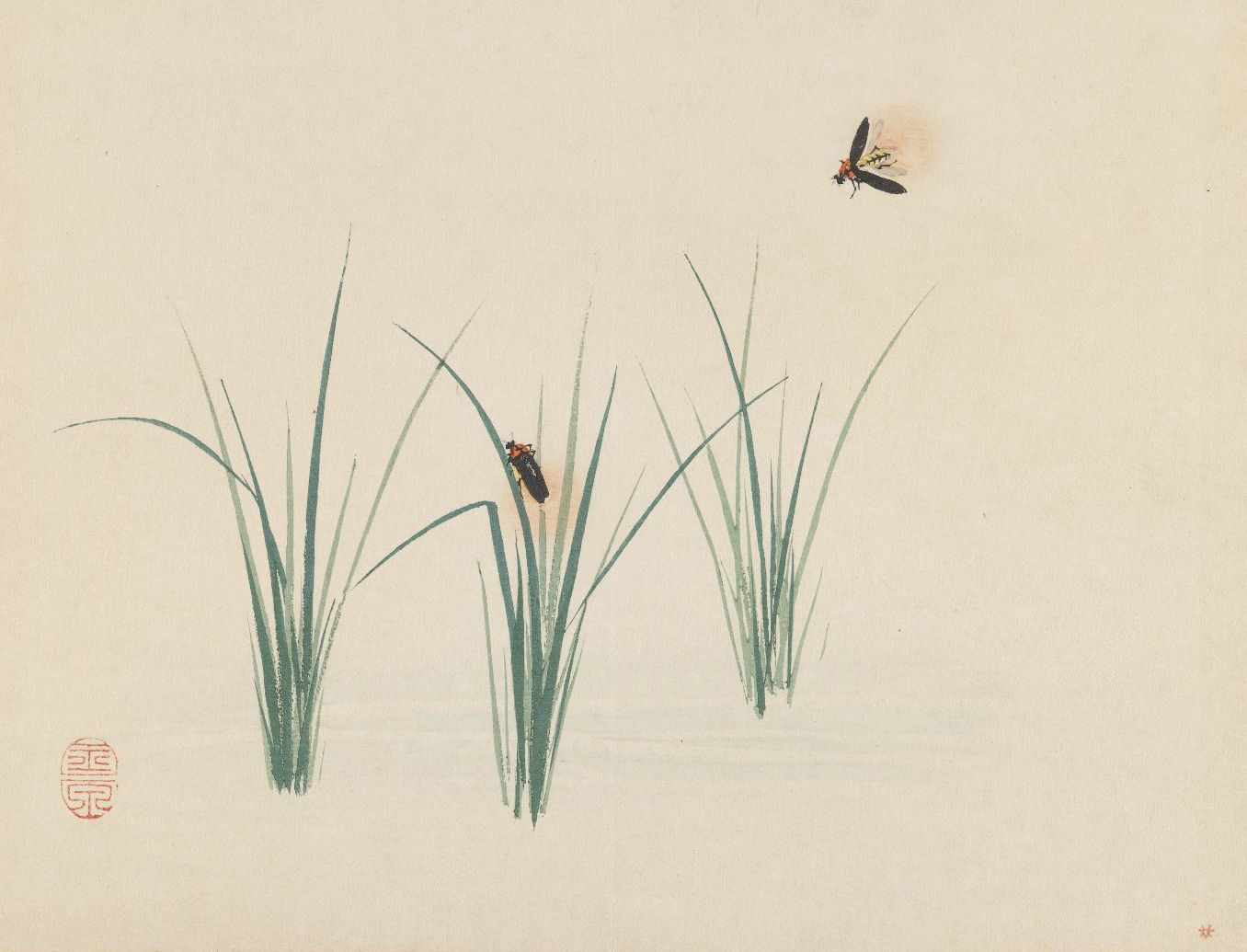

As the sun sets on the warmest nights of summer, the air becomes alive with the blinking lights of fireflies. They love the weather that can make the city feel especially oppressive, the heat and the humidity.

While there are thousands of species of fireflies, the one you’re most likely to witness in New York City is the common eastern firefly—Photinus pyralis—sometimes called the big dipper firefly, as the male’s light pattern can appear like an illuminated J as it flies, trying to find a mate with these rhythmic semaphores. (And on clear summer nights, you can easily see the Big Dipper constellation up in the stars. Can you find it above? Do any stars twinkle in response to these tiny beetles hovering just above the ground?) Their green-yellow bioluminescence comes from the chemical reaction of luciferin and luciferase on the tiny “lantern” they carry on their abdomen.

The yearly populations of fireflies can be difficult to predict; sometimes they get fooled by the early warmth of spring and then cannot survive the sudden cold. Other years with plenty of rain allow them to flourish. If you remember seeing them in more bountiful numbers as a kid, you may not be wrong. They have experienced a recent decline due to light pollution that can interfere with their signaling, insecticides, and a loss of the habitats where they need to spend time underground as juveniles.

But on those summer nights, the kind where you’d rather stay out long beyond sunset than return home, you can find them. They love the parks, like all New Yorkers in summer, but they also love the empty lots and cemeteries where fewer people are there to disturb their mating rituals. Walk some evening by Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn and watch them emerge over the monuments and tombstones and sculpted angels like spirits resurrected.

- Firefly or lightning bug? According to a map from NC State University’s Department of Statistics, New York is a state where they are used interchangeably. The West Coast tends towards firefly and the Midwest to lightning bug, but some places seem to like them both too much to choose.

- The city is full of messages in light that are easy to overlook. Next time you take the subway, notice the signal lights used by the train operators. Just like a traffic light, red is stop, green is go, and yellow is go with caution. Some of the signaling equipment in use dates back to the 1930s! (Leading to, surprise, delays.)

- There are many species of street lights in our fair city. The NYC Street Design Manual lists 13 types of standard, distinctive, and historic poles and 11 varieties of “luminaries”—which happen to be rated using the BUG system (Backlight, Uplight, and Glare). The possible combinations create a matrix that includes the octagonal pole with the cobra head luminaire, the arty Bishops Crook pole (first introduced in 1900 on narrow streets) with teardrop luminaire, and the World’s Fair Pedestrian Pole (originally installed in the 1964 extravaganza, but now present in many parks and pedestrian walkways) with the 2085 luminaire.