A Toxic Green Flourishes

“MARGO! COME BACK! THEY SAID IT’S BAD NOW!” shouts a man, as a labradoodle bounds into the miasma of a park lagoon. Margo hesitates. Reluctantly, she sloshes back through a vivid suspension of green on green—antifreeze floating on Mountain Dew and swirled with slime. It is the time of Harmful Algal Blooms.

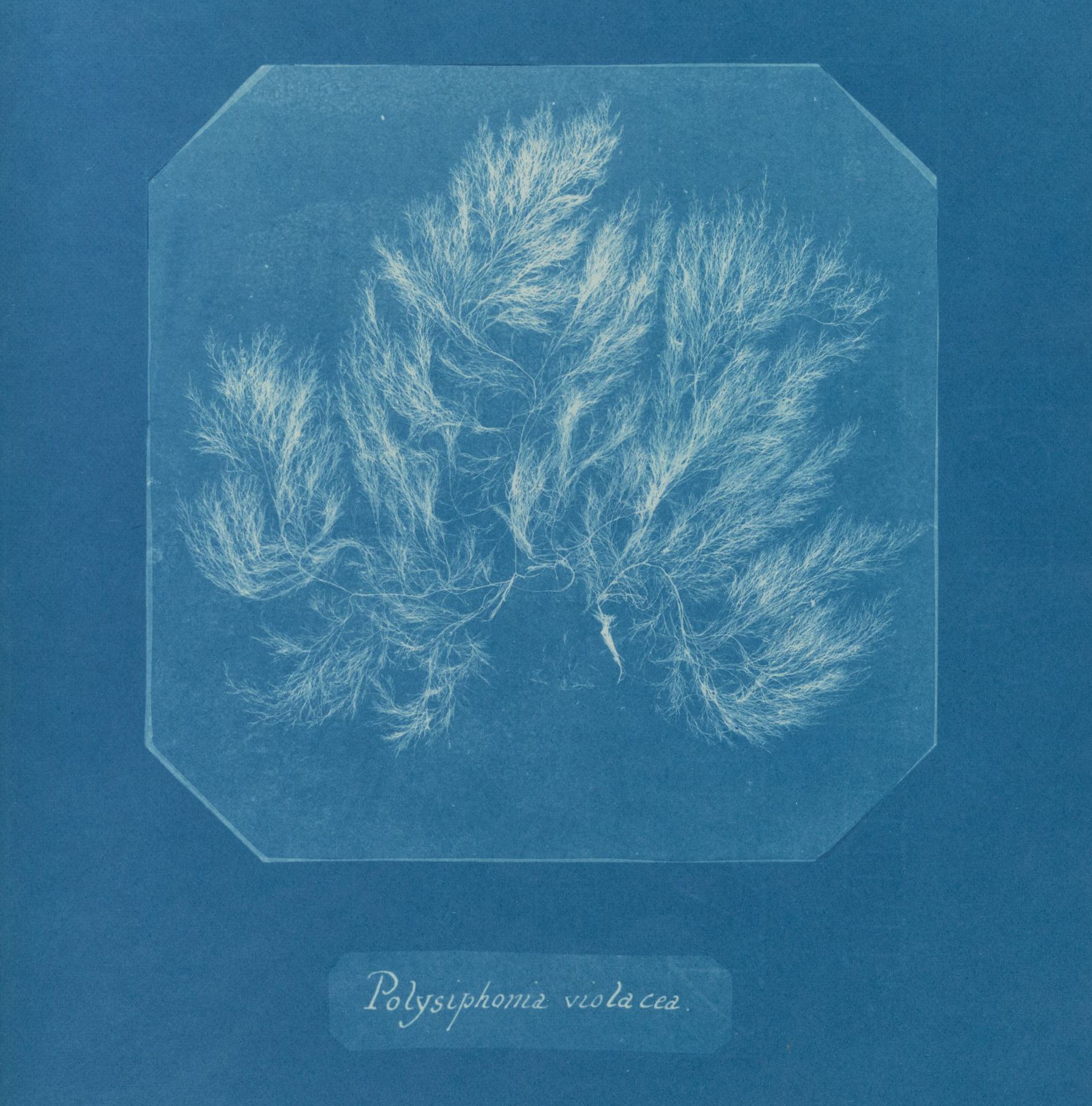

Cyanobacteria (or blue-green algae) evolved two billion years ago, with never a thought of humans or dogs. But as they thrived those eons ago, they added oxygen to our atmosphere, making humans and dogs possible in the first place. Cyanobacteria live in almost every part of the world—swimming in the seas, clinging to Antarctic rocks, clasping desert sands—and most species are vital to healthy ecosystems. Some cyanobacteria, though, produce toxins. Exactly why is still a mystery, but the effects they induce run the gamut from rashes to respiratory paralysis. Dogs are particularly susceptible because of their propensity for a fearless plunge and their inability to read posted signage.

City parks are perfect cauldrons for these toxic potions. Many bodies of water are man-made—limpid pools self-consciously mirroring carefully constructed vistas. Their shallow waters quickly warm in the summer sun’s ministrations, becoming aquatic hothouses for algal blooms. Fertilizer flows in the form of our tap water. An additive called orthophosphate helps prevent lead leaching from aging pipes, but also trickles into pools and ponds fed by the city’s water system. The cyanobacteria flourish in that nutritious phosphatic stew.

Buy a kiddie microscope. Take your own lake sample and slide it under the lens. A new landscape swims before you. Specks resolve into colonies and different species form different shapes. You’re holding your breath while you stare, but when you next inhale, recognize that some of that oxygen comes from what you see before you. Just don’t let your labradoodle get into the water.

- Keep your eyes peeled for the Prospect Park Lake Weed Harvester, aka The Floating Goat (named in honor of the park’s other professional weed eaters, the resident goat herd). Manned by a small crew, this vessel churns through the waters, slurping up aquatic weeds like floating water primrose and duckweed that can clog up the surface and starve the lake of oxygen. Back on land, the invasive plants are mulched for use in the park.

- Some of the city’s waterways may be bad for potential swims now, but they were abysmal in the mid-century before the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency. Pollution in the city got especially dire from November 23 to 26, 1966, when smog settled over the city, driving people indoors and leading to the deaths of an estimated 168. And yet the Macy’s Day Parade went on, the balloons soaring through a malodorous gray haze.

- The making of an unnatural waterway requires a lot of labor: all of the streams, waterfalls, and the big lake in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park were excavated by human hands. Although aided by some 19th-century earthmoving machines (the bulldozer wouldn’t have its heyday of earthmoving until after WWII), it was mostly the toil of their hours that resulted in these watery landscapes that now harbor cyanobacteria. Think of them as you walk safely on the shores.